What is Gevurah and why is it often so misunderstood?

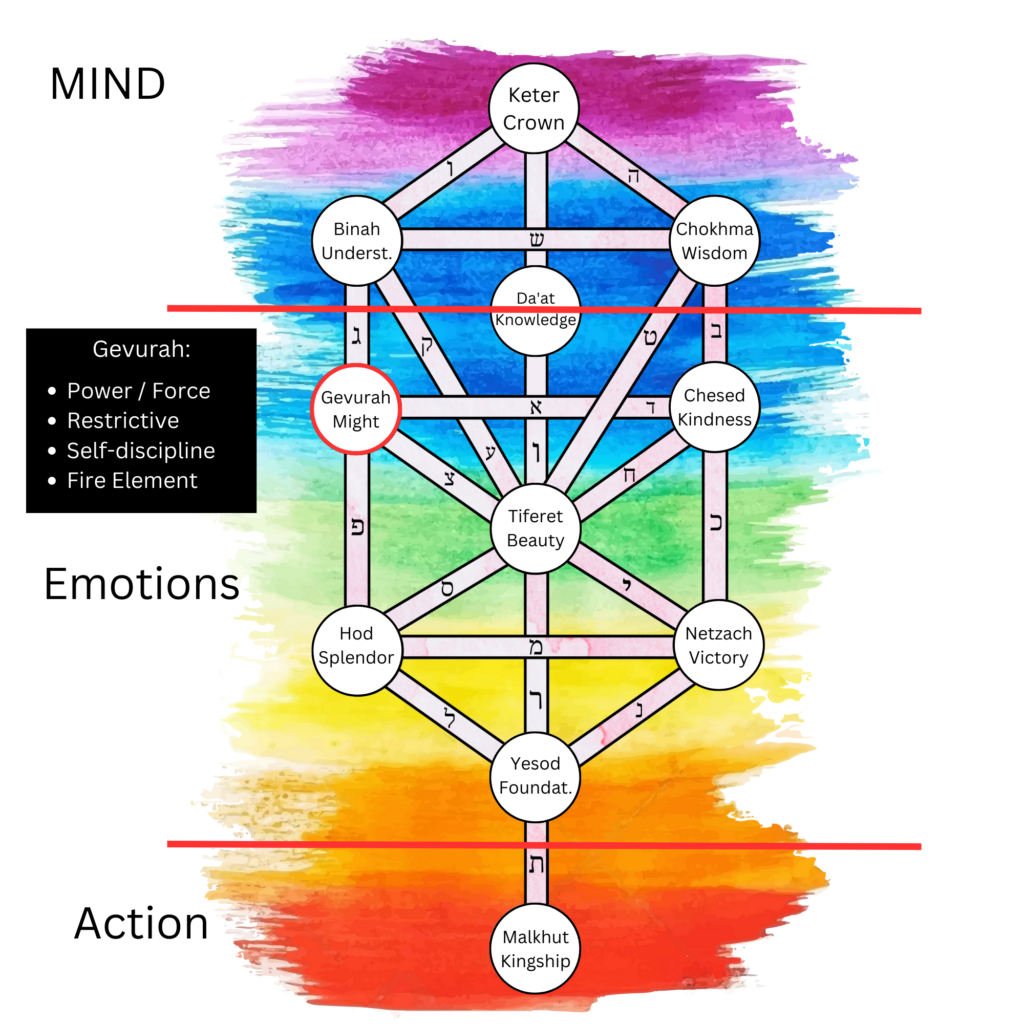

Gevurah, the fifth Sefirah in the Tree of Life, is often reduced to only harshness or wrath. In truth, it is one of the most essential Divine attributes, representing strength, restraint, precision, and judgment. It is Gevurah that enables Chesed to be meaningful.

Without it, Divine abundance would flow without limit and destroy the very structure of creation as we wouldn’t have free will and nothing could be differentiated. The Zohar (I:22a) describes Gevurah as the “left arm” of God, balancing the expansive “right arm” of Chesed. This left arm doesn’t just reject, but also defines. It creates boundaries, allowing light to be received in proper measure.

The Midrash (Bereishit Rabbah 12:15) teaches that Hashem initially intended to create the world with the attribute of Din alone, but saw it would not endure, so He joined it with Rachamim (mercy). This reveals that Gevurah is not a secondary or corrective trait, but part of the Divine blueprint. It is what allows for responsibility, justice, and moral structure in the universe. A world tempered by Gevurah stands firm, measured, and capable of holding the Divine light within vessels as we will soon explore its many facets.

This article is part of the Tree of Life series:

- Sephira of Keter

- Sephira of Chokhmah

- Sephira of Binah

- Sephira of Da’at

- Sephira of Chessed

- Sephira of Gevurah

- Sephira of Tiferet

- Sephira of Netzach

- Sephira of Hod

- Sephira of Yesod

- Sephira of Malkhut

Gevurah as the Left Arm of Hashem

When the Zohar defines Gevurah as the left arm of Hashem, this isn’t merely poetic symbolism. The left side, in Kabbalistic tradition, always represents contraction and limitation, while the right side represents expansion and generosity. Gevurah, therefore, acts as the necessary contraction that contains and channels the flow from Chesed. The Arizal explains in Eitz Chaim (Shaar 12) that without Gevurah, the light from above would pour forth in a way that the lower worlds could not endure, it would destroy rather than sustain.

By introducing boundary and withholding, Gevurah gives spiritual light a vessel. It defines the lines between what is sacred and what is profane, what is permitted and what is not. In doing so, it upholds the very possibility of creation. This is reflected in the Halachic structure of Torah life: clear limits, times, and rules that create spiritual vessels. Every prohibition, every fence, every pause is an expression of Gevurah. It is the force that makes space for holiness by saying “no” when necessary.

The Divine Name Elokim and the Essence of Gevurah

The Divine Name Elokim is associated in Kabbalah with the Sefirah of Gevurah.

While the Tetragrammaton (Yud-Heh-Vav-Heh) expresses compassion and unbounded flow, Elokim represents justice, judgment, and measured interaction.

When one calls upon the Name Elokim, they invoke Divine clarity and discipline. In Shaarei Orah, Rabbi Yosef Gikatilla teaches that Elokim governs all the boundaries of nature and law. Through this Name, Hashem maintains exact balance in the world, providing according to what is earned, restraining where harm may arise, and exacting consequences that refine.

It’s worth repeating that the holy names give rise to the Sephirot and not the other way around. When the letters of the Hebrew alphabet are arranged in the spiritual worlds in the divine names that we know, they give rise to a certain expression of God’s will, which can be perceived in different ways.

On an individual level, Gevurah is the power to hold back, to judge correctly, and to act with responsibility and strength both toward others and ourselves.

Of course, too much of this Sephira would also make life impossible, as a person wouldn’t be able to have an impure thought and not be punished immediately.

Yet, when we study about the primordial vessels in Otzrot Chaim we find there were 2 main types of light that were emanated: Ohr Yashar (forward light, an aspect of compassion) and Ohr Chozer (returning light, an aspect of severity). In order for kelim (vessels) to be able to take place, the Ohr Chozer had to leave a Nitzotz (spark) into the vessel for it to solidify. In practical terms, only through restriction and severity can vessels be brought forth.

We don’t need to go into much explanations to understand what this means practically: a toddler needs to fall to learn how to walk, a person often needs to fail in business to finally reach success later on, an aspiring musician needs to fail to learn how to play properly, and of course, one needs to toil in Torah to become great.

These are signposts of the process, an aspect of constriction, and the way to build real vessels that won’t break.

Yitzchak Avinu as the Chariot of Gevurah

Yitzchak Avinu is described in the Zohar (I:137a) as the living embodiment of Gevurah. Where Avraham expressed Chesed through outreach and generosity, Yitzchak embodied inner strength, fear of Heaven, and disciplined restraint. His most defining moment, the Akeidah (Binding of Isaac), reveals the essence of Gevurah, not as passive suffering, but as an active surrender of the self to Divine will.

It’s also fascinating to see that Yitzhak Avinu’s account in the Torah is the shortest of the 3 patriarchs, showing that this Sephira must come in small measures. The Midrash Tanchuma (Vayera 22) teaches that Yitzchak not only accepted his role in the Akeidah but requested to be bound tightly, so that his body would not flinch and invalidate the offering. This is not weakness; this is supreme inner strength.

While Avraham was outward-facing, bringing others into his tent, Yitzchak focused inward, digging wells and rededicating paths already laid. His service reflected the concealed power of Gevurah, the ability to persist, to uphold truth in silence, and to maintain boundaries in a way that sanctifies reality.

The Zohar refers to Yitzchak as “pachad” (awe), not because he was frightening, but because he reflected the fear of Heaven itself. His silence was not emptiness but precision. In Yitzchak we see that Gevurah is not loud, it is exact, disciplined, and holy.

And yes, sometimes we also need to “abstain” from contact with others and cultivate our inner worlds.

Gevurah and the Boundaries of Holiness

One of the deepest functions of Gevurah is to create boundaries, which are essential to holiness. The Torah states, “You shall be holy to Me, for I, Hashem, am holy, and I have separated you from the nations to be Mine” (Vayikra 20:26). Rashi explains that holiness means separation. The Ramban on this verse expands further, teaching that kedushah arises from limiting oneself even in permitted areas.

In Kabbalah, this is the action of Gevurah: creating form by withholding, sanctifying through separation, and drawing lines that invite Divine presence. This, after all, is the essence of holiness (kedusha): separating one thing from another.

The same goes for Halachah which is an expression of Gevurah. Shabbat, kashrut, family purity, all involve limits, times, and boundaries. These are not restrictions in the modern sense, but channels for elevation. When one refrains from the forbidden or even restrains personal desires, they awaken holiness in the soul.

We find in the Zohar (III:83b) that true holiness comes from discipline, not indulgence. Gevurah makes room for the sacred by teaching us where not to go, what not to do, and how to refine even that which is permissible.

Sweetening the Judgments: How Gevurah Is Integrated

There’s a big misconception that Gevurah is bad, which has already been explained in another article.

The truth is it is not bad, but it often feeds evil. While it might appear harsh, in reality it must be integrated and sweetened. That means that the din is still there, but not as harmful as before.

In spiritual practice, this means overcoming one’s lusts and cravings for this world, while at the same time redirecting this energy above toward divine service. When one judges themselves fairly but kindly, or disciplines a child with care, they are enacting Gevurah tempered by love. This integration is part of the goal of all spiritual work since no one can really outrun the judgments.

Prayer is a prime example of this process. During Selichot and Yamim Nora’im, we approach Hashem with awe and trembling, acknowledging His attribute of Din, but we also appeal to His mercy. By doing so, we sweeten Gevurah, not by canceling it, but by elevating it. The Zohar (II:27a) says that when a person overcomes their own anger or holds back from revenge, they draw down mercy into the world.

These actions have unbelievable consequences, because human Gevurah, when aligned with Divine intention, repairs the harshness of judgment in the upper realms.

The Five Gevurot = Five Final Letters (ם ן ץ ף ך)

The Zohar teaches us that the five final letters of the Hebrew alphabet embody the five folds of judgment (gevurot). These five letters, which emerge at the end of words, symbolize severity or restriction because they “indicate the end”. Many of the Kavanot during prayer, especially during Rosh Hashanah is meant to sweeten these judgments.

Together their Gematria is 280, which spell the word פר, or [red] “cow”. From the Arizal there’s Kavanah in the verse before the Amidah “Adon-ai sefatai tiftach u’fi yaguid tehilatekha (God, open my lips so it may give you praise). Generally both Z”A and the Shekhina (Malkhut) have this פר dinim. However, once the Shekhina receives the 5 letters א from the 5 names of אהיה of Binah, it becomes sweetened, forming פרה (another allusion to the red heifer).

In summary, these gevurot, tzimtzum, hester, din, geder, mechitzah, are essential constraints. They do not suppress God’s light but regulate it, ensuring that creation can exist with both structure and freedom.

The Zohar also teaches a deep connection between the five Gevurot, the five constrictive judgments that manifest in the Sefirot, and the five redemptions that will unfold in the time of the Geulah (Final Redemption).

These five redemptions are embedded in the five expressions of redemption spoken by Hashem in Parashat Va’era (Shemot 6:6–8):

- “VeHotzeiti” – I will take you out

- “VeHitzalti” – I will rescue you

- “VeGa’alti” – I will redeem you

- “VeLakachti” – I will take you

- “VeHeveti” – I will bring you

Each Gevurah corresponds to a blockage or exile, and each redemption corresponds to the sweetening (המתקה) and elevation of that Gevurah:

- Gevurah in Chesed → Redemption from material bondage

When Divine kindness is constrained by judgment, it leads to material oppression and dependency. The redemption here is financial and physical freedom, being able to receive without servitude. - Gevurah in Gevurah → Redemption from fear and harshness

This Gevurah represents unmitigated severity. Its redemption is the release from inner fear, self-judgment, and external cruelty. It manifests as emotional and psychological healing. - Gevurah in Tiferet → Redemption from confusion and distortion of truth

Tiferet represents harmony and truth. When judgment corrupts it, clarity is lost. The redemption is a return to clear understanding, Torah consciousness, and emet (truth). - Gevurah in Netzach → Redemption from spiritual blockage and egoic ambition

Netzach is the drive to overcome, to achieve. When judgment enters, it turns into domination and stubbornness. The redemption is proper ambition, free from ego and spiritual blockage. - Gevurah in Hod → Redemption from shame and collapse of dignity

Hod represents acknowledgment and submission. When constrained by Gevurah, it results in shame and loss of confidence. Redemption here restores holy humility and spiritual dignity.

As one might imagine, this is not just about history or future prophecy. These five redemptions play out in your personal life. Every time you release yourself from fear, clarify truth, restore dignity, or shift from ego to purpose, you are participating in the tikkun of the Gevurot. Rebbe Nachman of Breslov also brings in his magnum opus Likutey Moharan that the only true appropriate fear is fear of God, all else are fallen, misplaced forms of fear.

This is the essence of redemptive work.

Concluding remarks

The path of Gevurah is not about punishment or denial but about power with purpose.

When we learn to harness this force rather than fear it, we step into the kind of inner strength that makes lasting transformation possible. Gevurah teaches us when to stop, when to say no, when to draw the line. It is the energy that allows us to uphold values, to contain light, and to break free from cycles of indulgence or confusion.

Without it, our spiritual growth remains vague. With it, we build vessels that can hold blessing.

The five Gevurot, when left unrectified, create layers of exile in our lives. But each one also contains the seed of redemption. When we engage Gevurah consciously, with kavvanah, awareness, and alignment, we begin to sweeten these judgments at their root. This is how personal redemption begins: one honest boundary, one act of clarity, one moment of self-restraint. And this is also how collective redemption moves forward.

The gates of Geulah don’t open with chaos, they open when judgment is sweetened into strength.

All the names of Yesod from the Second Gate of Shaarei Orah

English Name – Hebrew Name

God – Elohi”m אלהי״ם

Might – Gevurah גבורה

The Upper Court of Law – Beit Din Shel Ma’alah בית דין של מעלה

North – Tzafon צפון

The Dim Hand – Yad Keheh יד כהה

The quality of Harsh Judgment – Din HaKashah מדת הדין הקשה

The Supernal Court of Law – Beit Din HaElyon בית דין העליון

Merit – Zechut זכות

The Dread of Yitzchak – Pachad Yitzchak פחד יצחק

The Great Fire – Aish HaGedolah האש הגדולה

The Consuming Fire – Aish Ochlah אש אוכלה

Dominion – Memshalah ממשלה

Judgment – Din דין

Left – Smol שמאל

Gold – Zahav זהב

Bread – Lechem לחם

Salt – Melach מלח

Wine – Yayin יין

Darkness – Choshech חשך

Night – Laylah לילה

The Cloud – Anan ענן

The Thick Darkness – Arafel ערפל

Flesh – Bassar בשר

The Bee – Devorah דבורה

Fine Flour – Solet סלת

The Showbread Table – Shulchan שלחן

The Sun – Shemesh שמש

Fire – Aish אש

Sinai סיני

Justice – Mishpat משפט

Stone – Even אבן

Hand – Yad יד

The Copper Altar – Mizbe’ach HaNechoshet מזבח הנחשת

Earth – Adamah אדמה

God of Truth – Elohi”m Emet אלהי״ם אמת

Heaven – Shamayim שמים

Ruddy – Admoni אדמוני

The Arm – Zro’ah זרוע

The Vav – ו of The Name HaShem וא”ו של שם

Son – Ben בן

Ox – Shor שור

The Chamber of Hewn Stone – Lishkat HaGazeet לשכת הגזית

Terror – Pachad פחד

The Teru’ah Sound of the Shofar – Teru’ah תרועה

Fear – Yirah יראה

One Response

בס”ד

DÉCOUVRIR LE BUT DE LA GEVOURA DANS L’ORDRE DIVIN – LA PUISSANCE DE LA RETENUE ET LES 5 GEVOUROT

Qu’est-ce que la Gevoura et pourquoi est-elle si souvent mal comprise ?

La Gevoura, cinquième Sefira dans l’Arbre de Vie, est souvent réduite à la rigueur ou à la colère. En réalité, elle est l’une des qualités divines les plus essentielles, représentant la force, la retenue, la précision et le jugement. C’est la Gevoura qui donne sens à la Chesed (bonté), en la mesurant.

Sans Gevoura, l’abondance divine se déverserait sans limite et détruirait la structure même de la création : il n’y aurait ni libre arbitre, ni différenciation possible. Le Zohar (I:22a) décrit la Gevoura comme le « bras gauche » de Dieu, en équilibre avec le « bras droit » de la Chesed. Ce bras gauche ne fait pas que rejeter : il définit. Il crée des frontières, permettant à la lumière d’être reçue de manière mesurée.

Le Midrash (Berechit Rabba 12:15) enseigne qu’Hashem voulut initialement créer le monde avec la seule Midah de Din (rigueur), mais vit que le monde ne pourrait pas subsister ainsi. Il l’associa donc à la Rahamim (miséricorde). Cela révèle que la Gevoura n’est pas une qualité secondaire ou corrective, mais une composante fondamentale du plan divin. Elle permet la responsabilité, la justice et l’ordre moral dans l’univers. Un monde tempéré par la Gevoura est stable, mesuré, capable de contenir la lumière divine dans des récipients appropriés — comme nous allons le découvrir à travers ses multiples facettes.

Cet article fait partie de la série sur l’Arbre de Vie :

La Séfirah de Kéter

La Séfirah de ‘Hokhmah

La Séfirah de Bina

La Séfirah de Da’at

Sefira de Chesed

Sefira de Gevoura

La Gevoura comme bras gauche de Dieu

Lorsque le Zohar décrit la Gevoura comme le bras gauche de Dieu, ce n’est pas simplement une image poétique. Dans la tradition kabbalistique, le côté gauche représente toujours la contraction et la limitation, tandis que le côté droit symbolise l’expansion et la générosité. Ainsi, la Gevoura agit comme la contraction nécessaire qui contient et canalise l’abondance issue de la Chesed.

L’Arizal explique dans Eitz Ha’haïm (Sha’ar 12) que sans la Gevoura, la lumière supérieure se déverserait avec une telle intensité que les mondes inférieurs ne pourraient la supporter — elle détruirait au lieu de nourrir.

En introduisant une frontière, en retenant la lumière, la Gevoura lui offre un récipient. Elle trace les lignes entre le sacré et le profane, entre le permis et l’interdit. Elle rend ainsi la création possible. Cela se reflète dans la structure halakhique de la vie juive : des limites claires, des temps précis, des lois définies qui forment des récipients spirituels. Chaque interdiction, chaque barrière, chaque pause est une expression de Gevoura. C’est elle qui crée l’espace pour la sainteté, en disant « non » quand il le faut.

Le Nom Divin Elokim et l’essence de la Gevoura

Le Nom Divin Elokim est associé en Kabbale à la Sefira de Gevoura.

Alors que le Tétragramme (Youd-Heh-Vav-Heh) exprime la compassion et l’abondance illimitée, Elokim représente la justice, le jugement et l’interaction mesurée.

Quand on invoque le Nom Elokim, on appelle la clarté divine et la discipline. Dans Shaarei Ora, Rabbi Yossef Gikatila enseigne qu’Elokim gouverne toutes les frontières de la nature et de la loi. Par ce Nom, Hashem maintient un équilibre exact dans le monde, distribue selon le mérite, retient là où un mal peut survenir, et applique des conséquences qui affinent.

Il est important de rappeler que ce sont les Noms Divins qui donnent naissance aux Sefirot, et non l’inverse. Lorsque les lettres de l’alphabet hébraïque sont arrangées dans les mondes spirituels sous les formes des Noms divins que nous connaissons, elles donnent lieu à une certaine expression de la volonté de Dieu, perceptible de différentes manières.

Au niveau individuel : le pouvoir de se retenir

Sur le plan personnel, la Gevoura est la capacité de se retenir, de juger correctement, et d’agir avec responsabilité et force — envers les autres et envers soi-même.

Bien sûr, un excès de cette Sefira rendrait aussi la vie impossible : un individu ne pourrait même pas avoir une pensée impure sans être immédiatement puni.

Mais dans Otzrot ‘Haïm, on apprend que deux types principaux de lumière furent émanés : Ohr Yashar (lumière directe – compassion) et Ohr ‘Hozer (lumière réfléchie – rigueur). Pour que les kelim (récipients) puissent exister, le Ohr ‘Hozer devait déposer une nitzotz (étincelle) dans le récipient afin de le solidifier.

Concrètement, seules la restriction et la rigueur permettent de former des récipients stables.

On n’a pas besoin de longs discours pour comprendre ce que cela signifie dans la vie :

– un enfant doit tomber pour apprendre à marcher ;

– un homme échoue souvent en affaires avant de réussir ;

– un musicien doit se tromper avant de jouer juste ;

– et bien sûr, il faut peiner dans l’étude de la Torah pour devenir grand.

Ce sont là des repères du processus, des aspects de la contraction — et la manière de construire de véritables récipients qui ne se brisent pas.

Yitsḥak Avinou comme le Char de la Gevoura

Yitsḥak Avinou est décrit dans le Zohar (I:137a) comme l’incarnation vivante de la Gevoura. Là où Avraham exprimait la Chesed par l’accueil et la générosité, Yitsḥak représentait la force intérieure, la crainte du Ciel et la maîtrise de soi disciplinée. Son moment le plus marquant, l’Akeida (la ligature d’Yitsḥak), révèle l’essence de la Gevoura : non pas comme une souffrance passive, mais comme une soumission active de soi à la volonté divine.

Il est aussi remarquable que le récit de Yitsḥak dans la Torah soit le plus court des trois patriarches — montrant que cette Sefira doit se manifester en mesures limitées. Le Midrash Tanḥouma (Vayera 22) enseigne que non seulement Yitsḥak accepta son rôle dans l’Akeida, mais il demanda à être attaché fermement afin que son corps ne bouge pas et ne rende l’offrande invalide. Ce n’est pas de la faiblesse : c’est une force intérieure suprême.

Tandis qu’Avraham était tourné vers l’extérieur, accueillant les autres sous sa tente, Yitsḥak se concentrait sur l’intériorité : il creusait des puits et redédiait les sentiers tracés. Son service reflétait le pouvoir caché de la Gevoura : la capacité de persévérer, de maintenir la vérité dans le silence et de poser des limites qui sanctifient la réalité.

Le Zohar appelle Yitsḥak « Pachad » (crainte), non parce qu’il inspirait la peur, mais parce qu’il reflétait la crainte du Ciel elle-même. Son silence n’était pas vide, mais précis. En Yitsḥak, on voit que la Gevoura n’est pas bruyante, elle est exacte, disciplinée, sainte.

Et oui, parfois, il nous faut aussi « nous abstenir » de tout contact, pour cultiver notre monde intérieur.

Gevoura et les Frontières de la Sainteté

L’une des fonctions les plus profondes de la Gevoura est de créer des limites — ce qui est essentiel à la Kedoucha (sainteté). La Torah déclare :

« Vous serez saints pour Moi, car Moi, Hachem, Je suis saint, et Je vous ai séparés des peuples pour que vous soyez à Moi » (Vayikra 20:26).

Rachi explique que la sainteté signifie la séparation. Le Ramban va plus loin et enseigne que la Kedoucha provient d’une retenue même dans ce qui est permis.

En Kabbale, cela incarne l’action de la Gevoura : former par la retenue, sanctifier par la séparation, tracer les lignes qui invitent la Présence divine. Telle est l’essence de la sainteté : séparer une chose d’une autre.

Il en va de même pour la Halakha, qui est une expression de Gevoura : le Chabbat, la cacherout, la pureté familiale — toutes ces lois impliquent des limites, des temps, des frontières. Il ne s’agit pas de restrictions dans le sens moderne, mais de canaux pour l’élévation. Lorsqu’une personne s’abstient de l’interdit, ou même retient ses désirs, elle éveille la sainteté dans son âme.

Le Zohar (III:83b) enseigne que la vraie sainteté vient de la discipline, non de l’indulgence. La Gevoura ouvre l’espace pour le sacré en nous apprenant où ne pas aller, quoi ne pas faire, et comment raffiner même ce qui est permis.

Adoucir les Jugements : L’intégration de la Gevoura

Une idée fausse courante est de croire que la Gevoura est mauvaise. En vérité, elle n’est pas mauvaise, mais lorsqu’elle est isolée, elle peut alimenter la sévérité excessive, voire le mal.

La Gevoura doit être adoucie (hamtaka) et intégrée. Cela signifie que le Din est toujours présent, mais sous une forme adoucie. Dans la pratique spirituelle, cela se traduit par la capacité à dominer ses pulsions, et à rediriger cette énergie vers le service divin.

Quand une personne se juge elle-même avec équité mais aussi avec miséricorde, ou discipline un enfant avec bienveillance, elle incarne la Gevoura tempérée par l’amour. Cette intégration est l’un des objectifs fondamentaux du travail spirituel : on ne peut échapper aux jugements, mais on peut les élever.

La prière en est un exemple majeur. Pendant Seliḥot et les Yamim Noraïm, nous approchons Hachem avec crainte, reconnaissant Son attribut de Din, mais en faisant appel à Sa miséricorde. Ainsi, nous adoucissons la Gevoura — non en l’annulant, mais en l’élevant. Le Zohar (II:27a) enseigne que lorsqu’une personne surmonte sa colère ou retient sa vengeance, elle attire la miséricorde dans le monde.

Les effets en sont immenses : la Gevoura humaine, alignée sur la volonté divine, répare la sévérité dans les sphères supérieures.

Les Cinq Gevouroth = Les Cinq Lettres Finales (ם, ן, ץ, ף, ך)

Le Zohar enseigne que les cinq lettres finales de l’alphabet hébraïque incarnent les cinq formes de jugement (Gevouroth). Ces lettres apparaissent à la fin des mots et symbolisent la restriction, car elles marquent la fin.

Leur guematria commune est 280, soit פר (vache). D’après l’Arizal, il existe une kavana dans le verset précédant la Amida :

« Ado-naï sefataï tiftah oufi yaguid tehilatekha » (Éternel, ouvre mes lèvres et ma bouche proclamera Ta louange).

En général, Ze’ir Anpin et la Shekhina (Malkhout) contiennent ces 280 jugements (dinim). Mais lorsqu’on associe à la Shekhina les cinq lettres א des cinq noms Ehyeh de Bina, cela les adoucit, formant alors פרה (la vache rousse), symbole de purification.

Rédemption et Gevoura

Le Zohar enseigne aussi un lien profond entre les cinq Gevouroth — ces jugements restrictifs — et les cinq expressions de rédemption prononcées par Hachem dans la Paracha Vaera (Chémot 6:6–8) :

VeHotzeiti – Je vous ferai sortir

VeHitzalti – Je vous délivrerai

VeGa’alti – Je vous rachèterai

VeLakachti – Je vous prendrai

VeHeveti – Je vous amènerai

Chaque Gevoura correspond à une forme d’exil, et chaque rédemption à une élévation ou adoucissement :

Gevoura dans Chesed → Rédemption de la servitude matérielle

Gevoura dans Gevoura → Rédemption de la peur et de la cruauté

Gevoura dans Tiferet → Rédemption de la confusion et de la perte de vérité

Gevoura dans Netzach → Rédemption de l’ambition égotique

Gevoura dans Hod → Rédemption de la honte et de la perte de dignité

Ce processus n’est pas que cosmique ou historique. Il est vécu dans la vie personnelle : chaque fois qu’on se libère d’une peur, qu’on restaure la vérité ou qu’on retrouve sa dignité, on participe à la tikoun des Gevouroth.

Rabbi Naḥman de Breslev enseigne dans le Likouté Moharan que la seule crainte véritable est celle d’Hachem ; toutes les autres sont des peurs déplacées ou déchues.

Conclusion

Le chemin de la Gevoura n’est pas celui de la punition, mais celui de la puissance maîtrisée.

Apprendre à l’utiliser plutôt que la redouter, c’est accéder à une force intérieure capable de transformation véritable. La Gevoura nous apprend quand s’arrêter, quand dire non, quand poser des limites. C’est l’énergie qui permet de préserver les valeurs, de contenir la lumière, de sortir des cycles d’excès ou de confusion.

Sans Gevoura, la croissance spirituelle reste floue. Avec elle, on construit des récipients capables de contenir les bénédictions.

Les cinq Gevouroth, si elles ne sont pas réparées, forment des exils dans nos vies. Mais chacune contient en elle la semence de sa propre rédemption. En engageant la Gevoura avec kavana, conscience et alignement, on commence à adoucir les jugements à leur racine.

C’est ainsi que commence la guéoula personnelle : une limite juste, un moment de clarté, un acte de retenue. Et ainsi avance aussi la guéoula collective.

Les portes de la rédemption ne s’ouvrent pas dans le chaos — elles s’ouvrent quand le jugement est adouci en force sacrée.